Wednesday, 10. January 2024

During an acute asthma attack, the small airways constrict to such an extent that normal breathing is significantly impaired. And then panic is added into the mix. More conscious breathing can mitigate respiratory distress. The physiotherapist and respiratory therapist Marlies Ziegler explains how to practise conscious breathing and how to use it.

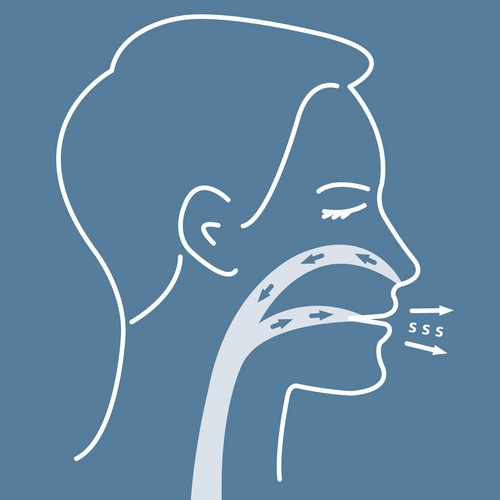

During an acute asthma attack, the small airways severely constrict. Anyone having an asthma attack cannot breathe out properly, which then shifts the breathing pattern. They take shorter breaths and the rate of breathing is also faster. This prevents them from breathing in fresh, oxygen-rich air. Added to this is the fear of suffocation, which leads to faster and less effective breathing. It is only after they inhale an asthma spray that relaxes and dilates the bronchial tubes that they can breathe properly again.

So that it doesn’t get to that, or to mitigate the asthma attack, patients can try the following if they feel an asthma attack coming on: reducing the breathlessness and panic with conscious breathing. Because breathing consciously and properly supplies the body and brain with more oxygen. This relaxes the body and mind.

Anyone who has asthma should train conscious breathing so that they can call on the breathing technique if they have an attack.

This article was written in cooperation with Marlies Zieger. She works as a physiotherapist in private practice in Munich. She specialises in respiratory therapy. She has been treating patients with chronic obstructive and restrictive airway diseases such as asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis (CF) and primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), for more than 20 years.

Note: The information in this blog post is not a treatment recommendation. The needs of patients vary greatly from person to person. The treatment approaches presented should be viewed only as examples. PARI recommends that patients always consult with their physician or physiotherapist first.

An article written by the PARI BLOG editorial team.

© 2024 PARI GmbH Spezialisten für effektive Inhalation