Shortness of breath or just air hunger? Prof. Fischer explains what brings this on and the role of treatments, inhalation therapy and training.

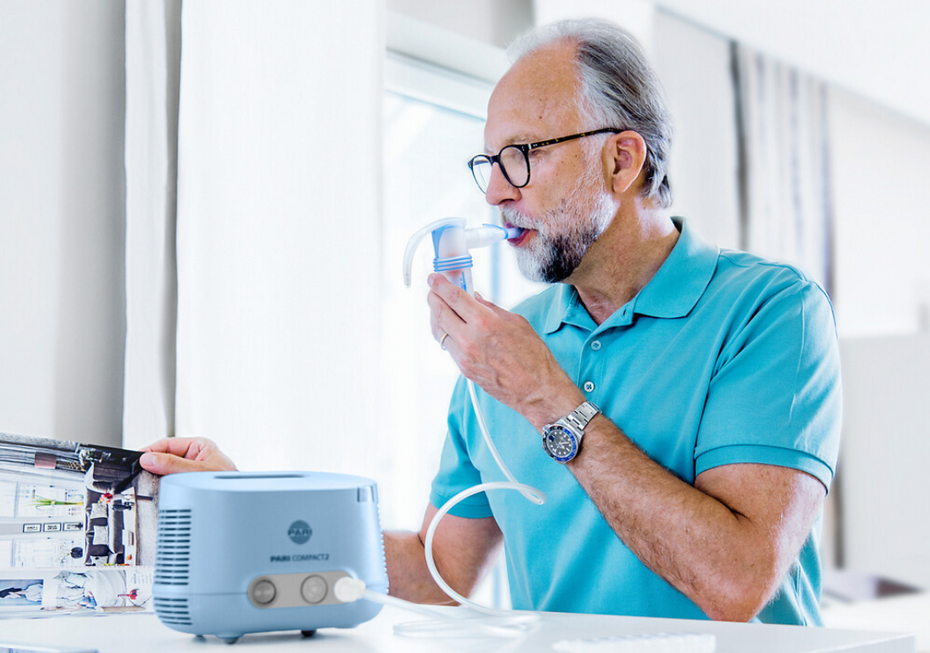

Shortness of breath can have many faces: from harmless air hunger to serious diseases that have to be treated immediately. In the interview, the lung specialist Prof. Rainald Fischer explains how you can tell the difference, the causes of shortness of breath and why exercise is still important, despite the symptoms. With obstructive pulmonary diseases, the first line of treatment is to inhale bronchodilators that make it easier to breathe. Inhaling saline solutions can be used as an additional therapy to liquify mucus and moisten the airways. This can also help support breathing.

Prof. Dr Fischer: We have to draw a distinction. On the one hand, we have real shortness of breath, which is associated with too low oxygen saturation and is an emergency. On the other hand, many people talk about shortness of breath when what they actually mean is the feeling of being out of breath and getting less air than usual. This is something I would describe as air hunger.

It is the feeling that you can’t breathe in deep enough and that you still have to take another deep breath, even though your lungs are actually working well enough. Real shortness of breath is an emergency and requires treatment. Air hunger is a temporary state that is not concerning.

Added to this, shortness of breath is a very non-specific symptom. It can be caused by diseases of the lungs, the heart or the muscles. This means it is often not easy to identify the cause. Sometimes, no clear explanation is ever found.

Prof. Dr Fischer: In healthy people, the lungs are not usually the problem. They can absorb enough oxygen and expel carbon dioxide. It is usually the cardiovascular system that is limiting. The heart cannot manage to transport the blood and waste products quickly enough. Someone suffering from real shortness of breath on exertion will tend to have lung, heart or muscle disease. But if someone just gets out of breath quickly and experiences air hunger, they are usually just not fit enough.

Prof. Dr Fischer: A good everyday example to tell the difference between the two is climbing the stairs: If you have to stop after a single flight of stairs because you can feel that your body is not getting enough oxygen, your lips or fingernails turn blue, this is generally a sign of real shortness of breath. Even if the shortness of breath comes on suddenly when you exercise or has only just started – for example, if you were able to go up two flights of stairs just a week ago without any problems and now you need to take a break – it is very important that you see a doctor. If shortness of breath comes on gradually over weeks or months, this is also an important warning signal.

Prof. Dr Fischer: Shortness of breath is a very non-specific symptom. The spectrum is very wide. Lung diseases such as asthma or COPD, the aftereffects of acute respiratory infections such as flu or COVID-19 as well as heart or muscular diseases may be involved. Sometimes it is not possible to identify the cause, even with detailed examinations. If someone has air hunger, the cause is often just lack of exercise or being overweight.

Yet still: It is always good to clarify what is causing it. Life-threatening issues may also be the underlying cause for real shortness of breath: heart attack, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia or pneumothorax, which require immediate treatment.

Prof. Dr Rainald Fischer: In this case, you treat the underlying disease. For obstructive diseases such as asthma or COPD, you try to expand the bronchial tubes so that more air can flow through them. If, however, the alveoli are damaged – as is the case in end-stage COPD – the treatment options are sadly limited.

Exercise-induced shortness of breath can then either be managed by an external supply of oxygen or by adjusting the exertion or your own expectations. For example, you can still go up the stairs, just much slower to avoid becoming short of breath. Even with damaged lungs, you can still improve your exercise capacity and better control your shortness of breath with regular and suitable training. The goal is to stay active despite the limited lung function, to shape your own daily routine and to preserve your quality of life.

Prof. Dr Rainald Fischer: Yes, especially with COPD or other obstructive diseases. Here it is important to regularly loosen and remove the secretions to keep the airways free and allow more air in. Inhalation therapy and respiratory physiotherapy are helpful in these cases.

Prof. Dr Rainald Fischer: Inhalation therapy with a suitable inhalation device and hypertonic saline solution that liquifies the mucus, is a very effective method. The droplets the nebuliser generates are respirable and can reach the secretions in the bronchial tubes. The secretions are liquified and are easier to cough up. Many patients feel immediate relief as a result. Treatment can also be supported by physiotherapy techniques and devices such as the PARI O-PEP that helps remove secretions.

Prof. Dr Rainald Fischer: That’s a definite no. It is still important for a doctor to find out which organ is causing the shortness of breath. Generally speaking, exercise and training are always a good option that even people with advanced lung disease benefit from. Depending on the severity of the disease, it may be necessary to have extra oxygen support during the exercise.

Even under these conditions, training is strongly advised. This is because strong muscles not only improve your general stamina, but also help the body use its oxygen more efficiently. This helps prevent a vicious circle of inactivity, muscle loss and increasing shortness of breath.

Prof. Dr Fischer: It can be helpful, but readings taken with wearables should always be looked at closely. The devices take readings from your wrist and are therefore not always dependable. They can take false readings. With a little experience though, patients can certainly use the readings to assess their capacity. For exact readings, I recommend a simple finger pulse oximeter, which you can buy for just 30–40 Euros. It is important though, never to see the results in isolation, but always to look at the overall picture, and if in doubt to see a doctor.

Wearables such as smart watches or fitness trackers can measure your pulse, oxygen saturation and also movement patterns. For people with shortness of breath, this can certainly be helpful – although there are limitations. Readings taken from the wrist are prone to errors, so there are often artefacts – i.e. measuring errors caused by movement or poor contact with the skin. This is why these readings should always be interpreted with caution and, if in doubt, checked by a doctor.

Nonetheless, wearables can give helpful information. Some patients come to the practice with the readings from their watch, and you can actually sometimes gain information about relevant diseases, such as sleep apnoea, because their oxygen saturation drops repeatedly at night. But in other cases these readings are caused by measuring errors.

So wearables are suitable to regularly track your own results, ideally in combination with a more precise finger pulse oximeter. But is important to remember that the data cannot replace a medical examination, but rather can only be an additional aid.

Prof. Dr Rainald Fischer is a specialist for internal medicine in private practice, with a subspecialty in lung and bronchial medicine, specialty of emergency medicine, sleep medicine and allergy medicine in Munich-Pasing. Before that he worked as an internist and lung specialist, most recently as a senior physician at the Munich university hospital. Prof Dr Rainald Fischer is a founding member and president of the Deutschen Gesellschaft für Berg- und Expeditionsmedizin (German Society for Mountain and Expedition Medicine), and also a member of the Cystic Fibrosis Medical Association.

Note: The information in this blog post is not a treatment recommendation. The needs of patients vary greatly from person to person. The treatment approaches presented should be viewed only as examples. PARI recommends that patients always consult with their physician or physiotherapist first.